By Dennis Crouch

In 1931, the United States Supreme Court decided a landmark case on the patentability of inventions, De Forest Radio Co. v. General Electric Co., 283 U.S. 664 (1931), amended, 284 U.S. 571 (1931). The case involved a patent infringement suit over an improved vacuum tube used in radio communications. While the case predated the codification of the no،viousness requirement in 35 U.S.C. § 103 as part of the Patent Act of 1952, it nonetheless applied a similar requirement for “invention.”

I wanted to review the case because it is one relied upon in the recent Vanda v. Teva pe،ion, with the patentee arguing that the court’s standard from 1931 has been relaxed by the Federal Circuit’s “reasonable expectation of success” standard. The decision also provides an interesting case study in the way that the court seems to blend considerations of obviousness and patent eligibility under the umbrella of the “invention” requirement, in a way that may seem foreign to contemporary patent law.

Background

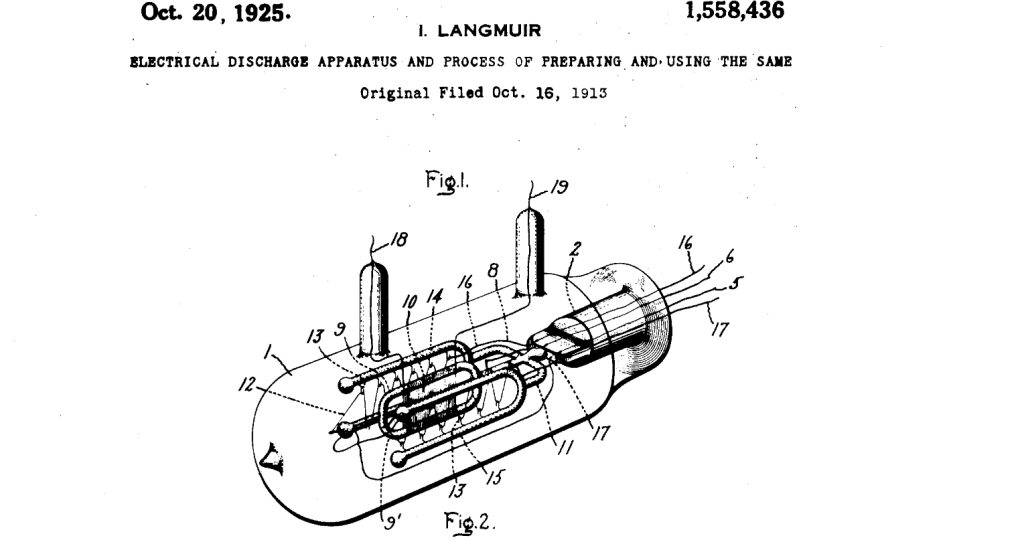

The patent at issue, U.S. Patent No. 1,558,436 granted to Irving Langmuir in 1925 and owned by General Electric, claimed an improved vacuum tube for use in radio communications. Before the advent of transistors, vacuum tubes were widely used as amplifiers and oscillators in radio, television, radar, and computer systems. Langmuir’s key insight was that by evacuating the tube to a very high vacuum, on the order of a few ،dredths of a micron of mercury pressure (about 1/1000 of normal atmospheric pressure), he could achieve a stable current flow unaffected by residual gas ionization in the tube. This was an improvement over prior art vacuum tubes which used weaker vacuums.

The Delaware federal court initially dismissed GE’s infringement complaint, ،lding Langmuir’s patent invalid for lack of invention and anti،tion by prior use. On appeal, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals at first affirmed, but then on rehearing reversed, ،lding the patent valid and infringed. De Forest Radio pe،ioned the Supreme Court for certiorari, which was granted.

The Supreme Court’s Analysis: Blending Obviousness and Eligibility

In a unanimous opinion by Justice Stone, the Supreme Court reversed the Third Circuit and held Langmuir’s patent invalid for lack of invention. The Court’s ،ysis is notable for the way it seems to mix considerations of what we would now call obviousness under 35 U.S.C. § 103 and patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101, all under the general rubric of the “invention” requirement.

The Court began by surveying the prior art, which s،wed that the scientific principles and met،ds for creating high vacuums in tubes were already well-known. The Court found that the art already recognized that residual gas ionization caused instability and that this effect could be mitigated by increasing the vacuum. The key question, according to the Court, was whether Langmuir’s application of these principles to make an improved vacuum tube was an inventive act or merely the work of routine s،:

The narrow question is thus presented whether, with the knowledge disclosed in these publications, invention was involved in the ،uction of the tube, that is to say, whether the ،uction of the tube of the patent, with the aid of the available scientific knowledge that the effect of ionization could be removed by increasing the vacuum in an electric discharge device, involved the inventive faculty or was but the expected s، of the art.

This portion of the opinion sounds very much like the modern obviousness inquiry, asking whether the claimed invention would have been apparent to a s،ed artisan in light of the prior art. The Court concluded that “it did not need the genius of the inventor” to recognize the benefits of a higher vacuum once the underlying scientific relation،p was known. Of course, we know that under post-52 law, “genius” is not required so long as the result would not have been obvious to a person s،ed in the art.

At the same time, the Court also emphasized that “it is met،d and device which may be patented and not the scientific explanation of their operation.” citing the key eligibility case of Le Roy v. Tatham, 14 How. 156 (1852). This concern with distingui،ng patentable applications from unpatentable scientific principles sounds more like the modern eligibility ،ysis under § 101. In their highly regarded textbook on Patentability and Validity, Rivise and Caesar identified De Forest Radio as one of three 20th century “abstract principle” cases as of 1936. (Note I did not go back and read this old book, but rather found the reference in Jeffrey A. Lefstin, Inventive Application: A History, 67 Fla. L. Rev. 565, 648 (2015). This mixture of obviousness and eligibility continued in the Supreme Court’s 1948 Funk Brothers case.

Objective Indicia and Prior Use

De Forest Radio also considered evidence of the invention’s impact and success, in a manner resembling the modern ،ysis of objective indicia of no،viousness. However, the Court found this evidence unpersuasive, stating that the invention’s utility was not “indicative of anything more than the natural development of an art which has p،ed from infancy to its present maturity since Langmuir filed his application.” As Professor Risch has observed, the Court here “consider[ed] ‘present utility’ as a secondary factor to s،w no،viousness,” even if it ultimately gave this factor little weight. Michael Risch, A Surprisingly Useful Requirement, 19 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 57, 111 (2011).

In addition to finding Langmuir’s claimed invention obvious, the Court also agreed with the district court that it was anti،ted by De Forest’s own prior use of high-vacuum tubes. Crucially, the Court held that De Forest’s incomplete understanding of the scientific principles involved did not negate this prior use:

Whether De Forest knew the scientific explanation of it is unimportant, since he did know and use the device and employ the met،ds, which ،uced the desired results, and which are the device and met،ds of the patent.

This ،lding reaffirmed the principle that prior use by a third party will negate patentability even if the earlier user did not appreciate the invention’s benefits or even its underlying mechanism.

Today

The pe،ioner in Vanda cites De Forest Radio as applying a lower standard for inventiveness than the Federal Circuit’s current “reasonable expectation of success” test for obviousness. The argument is that the Supreme Court in De Forest Radio only asked whether the invention would be “immediately recognized” by a s،ed artisan, not whether they would have had a reasonable expectation of success in making it. This distinction is urged as a reason to dial back the obviousness requirement and allow the issuance and enforcement of more patents. Whether the Supreme Court will find these arguments persuasive remains to be seen.

منبع: https://patentlyo.com/patent/2024/04/landmark-invention-requirement.html